When I hear a story, I am always curious to know the other side of the story!

Perhaps that can be traced to my training as a lawyer. As a young lawyer, when I’d hear the petitioner /plaintiff’s arguments, I’d feel it was an open and shut case. But then when the defence began with their arguments, I’d realize there was much more to the case!

This training has always prodded me to look for the other side of the coin and led me to discoveries that have broadened my horizon and deepened my understanding.

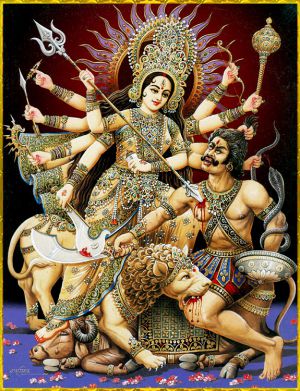

So this Dussera, while everyone will be talking about the story of Ram’s victory over Ravana and Durga’s victory over Mahishasura, the Buffalo Demon, here’s the other side!

Children of the Buffalo Demon

From the stotras we recite (Ayagiri Nandini) to the celebrations around us (Durga pandals) – the protagonist of the story is clearly Durga. But turn the tables around for a moment and you’d realize that Mahishasura may have a story too!

My quest to know the other side, led me to a fascinating discovery.

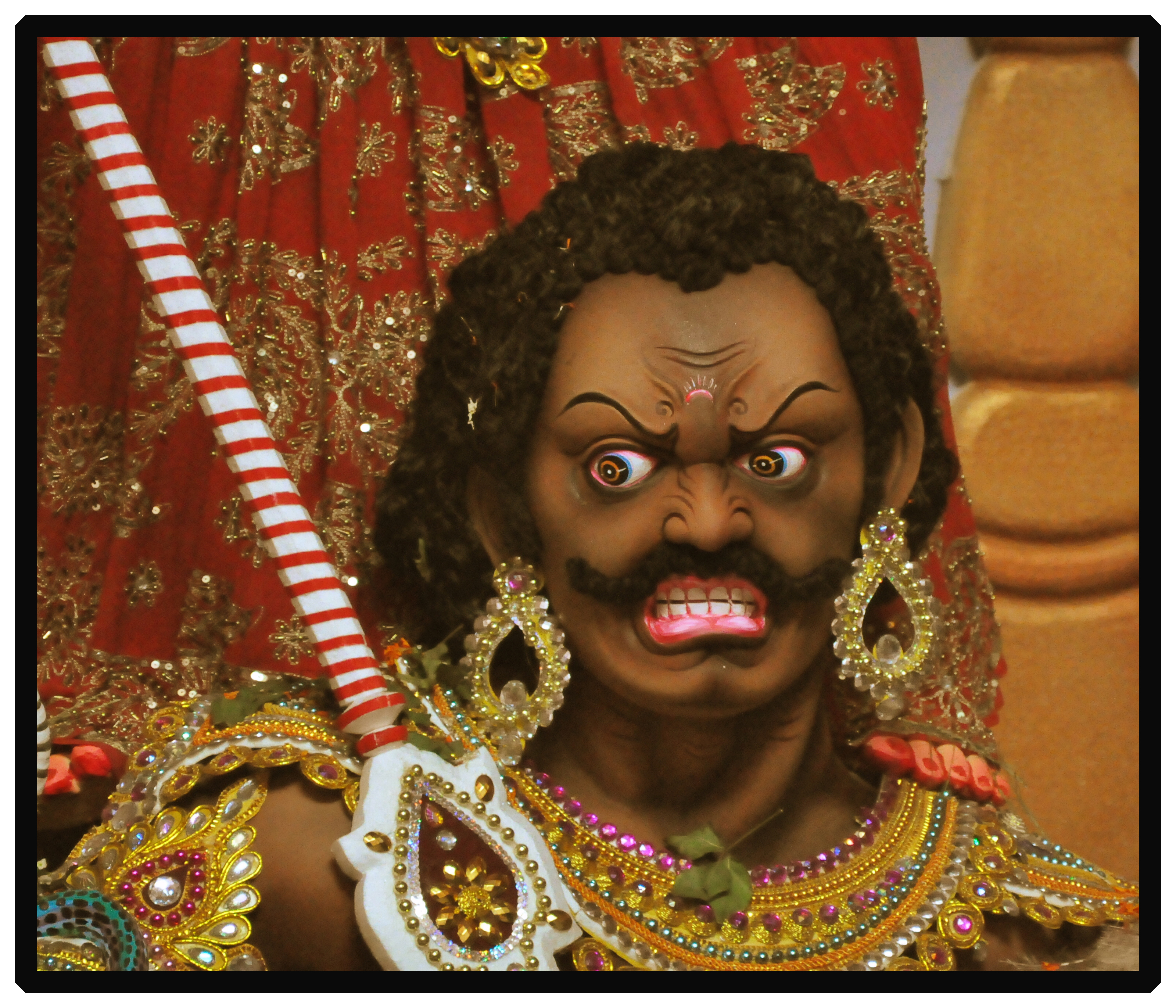

There is a tribe in Central India (today’s Jharkhand) which traces its ancestry to the mythical Mahishasura. They claim he was a tribal king, not a demon.

They are known as the Asur tribe.

Interestingly, people belonging to this tribe do not celebrate Navratri. For them, the nine days of Navratri are a period of mourning. For that is the time they lost their patriarch – Mahishasura, in a battle to Durga.

In fact a few days after Dussera, they mark a day called Mahishasura Smaran Divas to commemorate their forefather who was slain in battle.

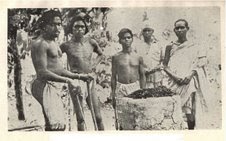

The Asurs are an Adivasi group that live in close proximity to and are often identified with the Mundas of Central India – although the two tribes have their differences.

While their story remained largely unknown in the mainstream for years, young people belonging to the Asur community are now coming out and speaking about their myths and stories.

They say that the popular narrative had them feeling ashamed of their ancestry for many years as Asuras are often painted in bad light in myths and stories. But a new generation is now taking the bull by its horns.

They take strong exception to the portrayal of Asurs as demons. They claim that Mahishasura was a native leader who was vanquished in battle as he refused to take up arms against a woman.

As History is written by the Victors, it is their case, that their voice has been drowned out of the popular narrative and their king demonized.

Their voices have now reached political and judicial circles and taken on a different edge – but that is beyond the scope of this story.

Anthropological Connections

There is a big debate on who the people termed as ‘Asuras’ in our myths really were. While some scholars have said they were the indigenous people of this land, others disagree with that analysis.

Whatever be the case, it is so that Asurs have been portrayed negatively in all the stories. Modern graphic novels further show them consistently as dark-skinned, hideous-looking, crude people.

The Asurs of Jharkhand say they have suffered for long due to these conditioned notions and want to reclaim their honour.

And one look at their contribution would convince all that they are anything but crude and horrifying.

It turns out that the Asurs have been practicing smelting of iron for centuries and they have great skill and know-how in manufacturing rust-free Iron. That has been their traditional occupation.

The famous Mehrauli Iron Pillar that stands beside the Qutub Minar in Delhi – famous for not having rusted despite having been around for over 1000 years, is a case in point about ancient smelting techniques of India, something that stumps modern day metallurgists too.

Could the techniques of the Asurs have been responsible for these great metal works of ancient India? How did the leader of these people get demonized in the stories? What is the history of these people?

These are questions begging for answers.

But we must nevertheless introduce children to these alternative stories.

Bertrand Russell, one of the great philosophers of the last century, says in one of his essays, that the purpose of an education is to have an open mind. Consequently, a process of learning that makes one dogmatic, defeats the whole purpose of education.

When one is exposed to alternate views, particularly those that challenge the popular narrative, whether one ultimately accepts or rejects them, it helps to widen one’s understanding of the world.

Alternative narratives help children to remain open minded, as they do not dismiss the other side of the story, merely because they haven’t heard it.

For instance, there are many Ramayanas. In some of them like the Jain Ramayana, Lakshmana, and not Rama, kills Ravana. In others, Sita is Ravana’s daughter. Multiple narratives. Multiple Dimensions.

But when we tell our children only one version of the story and continue to drum the same narrative over and over again, not only do we diminish their joy and understanding of these stories, we take away from one of India’s most beautiful features – its diversity.

Durga is worshipped. Mahishasura is worshipped. But without a dichotomy, we live on as one people. That diversity is one of India’s greatest strengths. Something worthy of passing on to our children.

And we live in an age when mythological fiction, containing popular stories are being told from alternate perspectives and catching on as a rage.

The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, is a beautiful telling of the Mahabharata from the perspective of Draupadi. I felt sad when I finished the book because I had enjoyed reading it so much!

Asura:Tale of the Vanquished: The Story of Ravana and His People by Anand Neelakanthan tells the story of the Ramayana from the perspective of Ravana. It offers a refreshing alternative perspective to the exactly same set of events of the Ramayana. Here, Sita is Ravana’s daughter, as she is in one of the many versions of the Epic.

Roll of the Dice: Duryodhana’s Mahabharata (Ajaya Book 1), also by Anand Neelakanthan, tells the story of the Mahabharata from Duryodhan’s (Suyodhana) point of view (contained in two volumes.) I fell in love with Duryodhan after this story and see the Mahabharata in whole new light.

Sita’s Sister and other stories by Kavita Kane look at the Epics through the eyes of smaller characters who had never counted for much so far. For instance, in Sita’s sister, Kane takes up the story of Urmila – whom Lakshmana left for 14 years as he accompanied Rama into the jungle. Lesser known characters come to life through these tales.

Of course all these are inspired by some great works in regional literature like Yuganta by Irawati Karwe (Marathi), Mrityunjaya by Shivaji Sawant (Marathi), Parwa by S.L.Byrappa (Kanada), The Liberation of Sita by Volga (Telugu) and so on. Some of these are also now available in English – and I would recommend them all very highly.

For children, Devdutt Pattanaik’s The Girl Who Chose: A New Way of Narrating the Ramayana tells the Ramayana from Sita’s standpoint. While Sita is seen largely as a victim, Devdutt sees her as the girl who made five choices – which form the turning point of the Ramayana.

For those looking for alternative narratives, there is plenty available.

Every coin must have two sides. All you need to do, is take the trouble to flip it over!

Hilton Beutler

March 19, 2019 - 10:41 pm ·I enjoy the efforts you have put in this, thankyou for all the great content.

Mallika Ravikumar

March 24, 2019 - 6:51 am ·Thanks for writing in and appreciating the the effort. That is very encouraging.